Since the publication of “Making Big Bets for Social Change” in Stanford Social Innovation Review just over three years ago, the topic of “big bet” philanthropy has been making headlines.

According to The Bridgespan Group, a big bet is an individual or foundation grant of $10 million or more made to a single organization or cause seeking to drive social change. These gifts have an extraordinary effect on organizations’ ability to expand their reach, improve the quality of their impact, strengthen their infrastructure, and deploy more resources in service of their mission.

Historically, most gifts of this magnitude were directed at traditional institutional recipients such as universities, hospitals, and large cultural institutions. With their robust development operations and compelling recognition opportunities such as named physical spaces and endowed chairs, these institutions regularly and effectively cultivate, solicit, and steward 8- and 9-figure gifts.

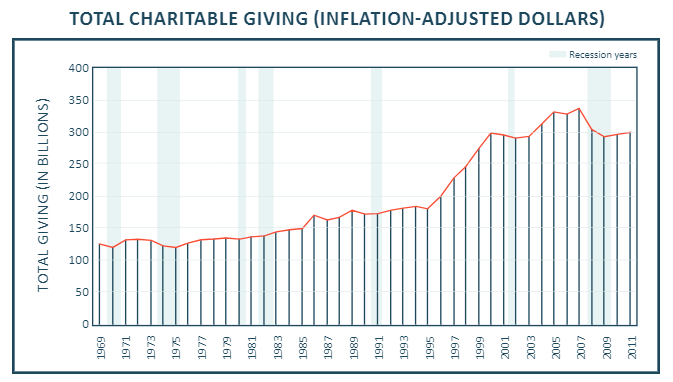

Yet with the rapid growth in wealth over the last two decades, we have experienced unprecedented levels of giving and a stronger commitment to bettering society, with an increasing number of big bets being made to support human services, environmental, and international development organizations. For example, in 2017, U.S. giving surpassed the $400 billion mark for the first time ever.[1] At the same time, the number of donors who made gifts of $25 million or more to social change organizations grew to 69, a significant jump from just 18 in 2000.[2]

The philanthropic landscape is ripe for big bets. Today, we stand at a pivotal moment in the history of philanthropy, as donors contemplate the impact that large-scale charitable investments can have on solving or dramatically improving persistent social problems.

So, what makes an organization “big bettable,” and how can organizations position themselves to secure significant eight and nine-figure investments in service of their mission?

In “Becoming Big Bettable,” William Foster, Gail Perreault, and Bradley Seaman discuss how a significant infusion of capital can transform an organization’s growth trajectory by dramatically scaling its resources, programs, and services. This positions the organization to take bigger, bolder steps to achieve its vital mission—from improving access to quality water to eradicating world hunger.

The key element of a big bet is an ambitious, measurable goal that demonstrates the specific results that can be achieved—and scaled—and that reflects the demand from communities, partners, policymakers, and other major stakeholders.

While the goal will typically be accomplished over a 5- to 10-year period, it will have enduring impact. Oftentimes, it occupies the “missing middle” that is more concrete than a long-term vision and more ambitious than a short-term goal. [3] Equally as important, the goal should matter not only to your organization, but also to society at large. How will your community, country, or even the world become a more just and inclusive place because of this bold investment?

At CCS, we have partnered with nonprofit leaders to tackle some of society’s greatest challenges. We have seen the extraordinary impact that big bets can have. And we know that accomplishing lofty goals requires allocating commensurate resources.

By developing a compelling investment concept with a clear and measurable goal, a strategic plan to get there, and a well-articulated role for philanthropy, your organization may be able to increase its opportunities of securing big bets and deploying them with distinctive impact. This, in turn, creates the potential for transformative social change.

Below are three steps your organization can take to position itself as big bet ready:

1) Identify a Societal Challenge that Demands Action and Innovation

“Big bettable” concepts address the core of some of society’s most persistent social challenges and are ripe for immediate action. What is the macro challenge your organization is trying to solve and how will a critical cash infusion scale the solution right now?

Since 1913, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) has fought to stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment to all. ADL remains on the frontlines against hate today through its anti-bias education and law enforcement training programs as well as grassroots advocacy to build a more civil society.

Today’s external environment demands a stronger ADL. In 2017, ADL reported a 57% surge in anti-Semitic incidents in the U.S.—the largest single-year increase on record since ADL started tracking such data in 1979.[4] This was compounded by the prolific volume of anti-Semitic and hateful content on social media platforms, where 4.2 million anti-Semitic tweets were shared or reshared in 2017.[5] At the same time, extremist activity made national headlines, from the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, VA, to the horrific massacre at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA, one year later.

From local schools to the halls of government to C-suites at Fortune 500 companies, society was crying out for a stronger, more innovative and impactful ADL. Yet the demand for ADL’s voice and expertise significantly outpaced its ability to deliver.

In order to best position your organization as big bettable, try to establish the urgent necessity of your mission in addressing specific issues, and the potential consequences of not rising to meet these issues, especially if they are of an escalating nature.

2) Develop an Ambitious, Measurable Goal with Enduring Impact

When donors bet big, it is because they are presented with an opportunity at an order of magnitude different from what they have been offered before—an investment concept that allows them to see the tangible possibility of enduring change in a distinctive way.[6]

Since his appointment as CEO of ADL in July 2015, Jonathan Greenblatt has applied his business acumen and entrepreneurial spirit to transform ADL—a 100+ year old institution—into a more innovative, impactful organization fighting anti-Semitism and all forms of hate on the frontlines.

In just a few years, Jonathan has built a best-in-class executive team with experts from the corporate, government, academic, and nonprofit sectors; revamped the organization’s governance structure from an over 300-member National Commission to a highly curated 16-person Board of Directors; and invested in measurement and evaluation to bolster ADL’s operational effectiveness. He also launched a fresh brand into the marketplace to ensure that ADL resonates not only with the organization’s stalwart supporters, but also with the next generation of leaders, advocates, and social entrepreneurs. And he’s just getting started!

Bold leaders dream big—and they bet big. They take a step back from the immediate organizational needs to consider the entire field they are trying to shift and inspire others to join them. “We stand at a pivotal moment in ADL’s history and a pivotal moment in our country’s history,” Greenblatt says. “We are making critical investments in our future to more effectively combat anti-Semitism and get ahead of the next technological trends to spread hate, including cyberhate.”

Greenblatt seeks to achieve this vision through transformational investments in ADL’s tools, talent, and technology. These growth capital investments will build critically needed capacity to measure and scale ADL’s education and advocacy programs to fight hate on the frontlines, pioneer cutting-edge tools to monitor and expose hate crimes and extremist threats with unrivaled efficiency and magnitude—on the ground and in our 24/7 digital environment, and develop technological and policy interventions to reduce the volume and impact of cyberhate.

ADL is an organization in transformation, and the deliberate steps that Greenblatt and his team have taken have positioned ADL to become “big bettable.” Through significant investments that build on its 100+ year record of success, ADL is poised to make critical strides in the fight against anti-Semitism and hate and create a more just and inclusive society.

When thinking about your organization’s goals, think about a new, lofty opportunity that is larger in scale and scope than what you’ve previously aimed to achieve and that builds on your past success. Be bold in sharing how big bet investments in your vision will dramatically change the status quo.

3) Inspire Donors to Bet Big on Your Vision

When donors consider making an exceptionally large investment, they generally want to do more than fund good work. They want to create change that solves or significantly improves a large-scale problem. The key to securing a big bet will rest on your ability to articulate why philanthropy is the missing ingredient for execution.

Big bets usually build on existing relationships. When Bridgespan analyzed a sample of 165 grants of $10 million or more from its big bets databases (gifts from U.S.-based donors to a social change organization or cause between 2000 and 2012), they found that the big bet recipients received a median of four previous grants from the donor prior to the big bet.

What does this mean for your organization? If a donor has given many times and at significant levels, chances are strong that he or she believes deeply in your mission and the people involved and may be poised to make a big bet. While it may not be a requirement to have a long relationship involving multiple gifts with every big bet donor, it is important to be patient and to play the long-game.

As fundraisers, we know that at the heart of any meaningful investment is a donor’s steadfast belief in the mission of the organization and trust in the CEO and his or her vision. To inspire donors to make the leap from a major gift to a big bet, organizations must emphasize the specific outcomes the donor’s investment will have, and how these outcomes will catapult the organization to a higher level of impact—but for this big bet, we would not have the resources or capabilities to achieve XYZ. It takes time and discipline, but the results are worth it!

For many donors, a big bet investment may be the single most consequential philanthropic commitment they make in their lifetime. Be bold and think big about the innovative and scalable solutions you seek to address society’s toughest challenges together.

CCS Fundraising is a strategic consulting firm that partners with nonprofits for transformational change. To access our full suite of perspectives, publications, and reports, visit our insights page.

[1] Snapshot of Today’s Philanthropic Landscape, 2018

[2] Unleashing Philanthropy’s Big Bets for Social Change, Introduction, 2019

[3] Unleashing Philanthropy’s Big Bets for Social Change, Becoming Big Bettable, 2019

[4] ADL Audit of Anti-Semitic Incidents, 2017

[5] Quantifying Hate: A Year of Anti-Semitism on Twitter, ADL, 2018

[6] Unleashing Philanthropy’s Big Bets for Social Change, Becoming Big Bettable, 2019